Why web archive research matters in the post truth age?

- Anat Ben-David

- Jun 12, 2017

- 3 min read

Originally published on "Talking Humanities"

Facts matter. In an age where the very notion of truth is under attack, where scientific knowledge is under scrutiny and critical journalism is considered “Fake News”, facts matter even more. But this age – recently dubbed as the age of “post truth” – is also a digital one. And while digital facts matter, born-digital facts are immaterial. Web data is fragile and easy to manipulate: the content of websites can be easily modified; tweets are frequently deleted; the number of Facebook comments and likes can be artificially boosted through click farms; and dubious sources spreading misinformation can be disguised as reliable news organizations.

The deterioration in the trustworthiness of the web as source of knowledge is also tied with its gradual commercialization. More than ever before, web data is primarily proprietary, and therefore subjected to platforms’ policies and constraints. Accessing raw data, with its full metadata, is becoming nearly impossible.

Given the fragility of web data, and the increasing difficulty to access it freely, how can we establish online evidence as facts, historical evidence, or truth?

Luckily, the Internet Archive is one of the last non-commercial knowledge devices that can be used to establish historical facts from web data. The Internet Archive captures snapshots of websites at a specific point in time and preserves them for eternity. Through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, one can browse the web’s past, and view pages that have been changed, removed, or deleted. Archived snapshots of websites serve as historical, born-digital facts. For example, the Internet Archive recently created a crowd-sourced collection that preserved federal government websites and data during the administration changes in the United States. But apart from the technical knowledge that explains how the Internet Archive captures websites, what do we know about the knowledge production process that constructs archived snapshots as facts? How does the Internet Archive ‘know’ what to capture and at which frequency?

The research project that my colleague Adam Amram and I will present in the upcoming RESAW Conference at the Web Archiving Week attempts to answer these questions. We unravel a complex socio-technical source contribution process behind what we eventually perceive as archived snapshots on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. As a case study, we focus on the Wayback Machine’s rare snapshots of North Korean websites.

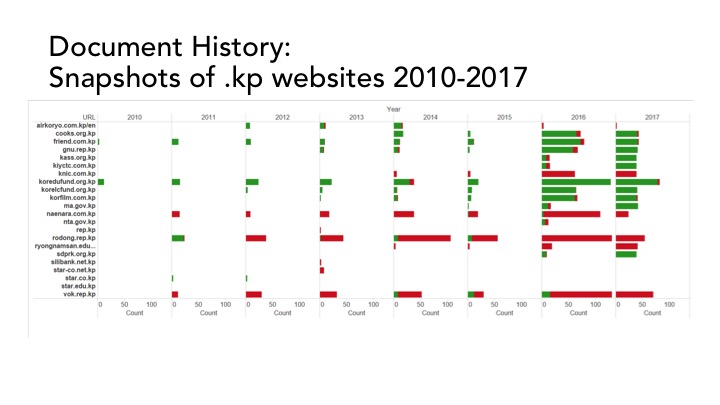

Although the .kp domain was delegated to North Korea in 2007, until recently little was known about its websites due to the country’s restrictive Internet policies. On 20 September 2016, an error in the configuration of North Korea’s name servers allowed the world to have a rare glimpse of 28 websites hosted in the .kp domain. However, we discovered that the Wayback Machine displays captures of these websites from as early as 2010.

How did the Internet Archive come to ‘know’ about the existence of the North Korean websites years before the DNS leak? To answer this question, we undertake a ‘forensic approach’ to web archive research. Focusing on the Wayback Machine’s new provenance information feature, we analyze the history of the sources that ‘informed’ the Internet Archive about the existence of the North Korean websites over time, and cross this information with an Internet censorship analysis that compares access to North Korean websites from different countries. Our analysis shows that although most of the websites have been contributed to the Internet Archive’s crawler by experts, activists and Wikipedians, the Internet Archive’s combination of a distributed and automated crawling system with globally-distributed source contributions result in a crowd-sourced knowledge culture that circumvents Internet censorship. As a knowledge device, the Wayback Machine is a ‘leaky archive’, in the sense that it accumulates scattered contributions over time, which eventually generates knowledge that is otherwise only accessible in times of DNS ‘leaks’. However, although globally informed, the fact that the Internet Archives’ crawlers capture the North Korean websites from servers physically hosted in the United States greatly affects the extent to which certain URLs can be archived, and also determines the scope of their archival coverage. Put differently, the Wayback Machine not only hosts successful captures of North Korean websites from as early as 2010, it also bears evidence of instances of failed attempts to access these websites from the United States.

This complicated history, combining global source contribution with the geopolitics that shape the web’s information flows, helps us to better understand the politics, the knowledge cultures and the constraints that shape the Wayback Machine’s contents. A deeper understanding of the Wayback Machine as a knowledge device only strengthens its importance as one of the Web’s last reliable repositories of born-digital historical facts.

Comments